FEBRUARY-MARCH 2024 - Part 1 - A Photograph

I am not sure of the year. The early fifties maybe? A photographer stands on the side of a small valley in the Montagne Noire. His camera, resting on a tripod, points north. It is summer but it was cool when he started out from Nîmes this morning and I imagine he is still wearing his light, knee-length, cotton coat and rather too fine, leather boots. His legs brace him against the hillside.

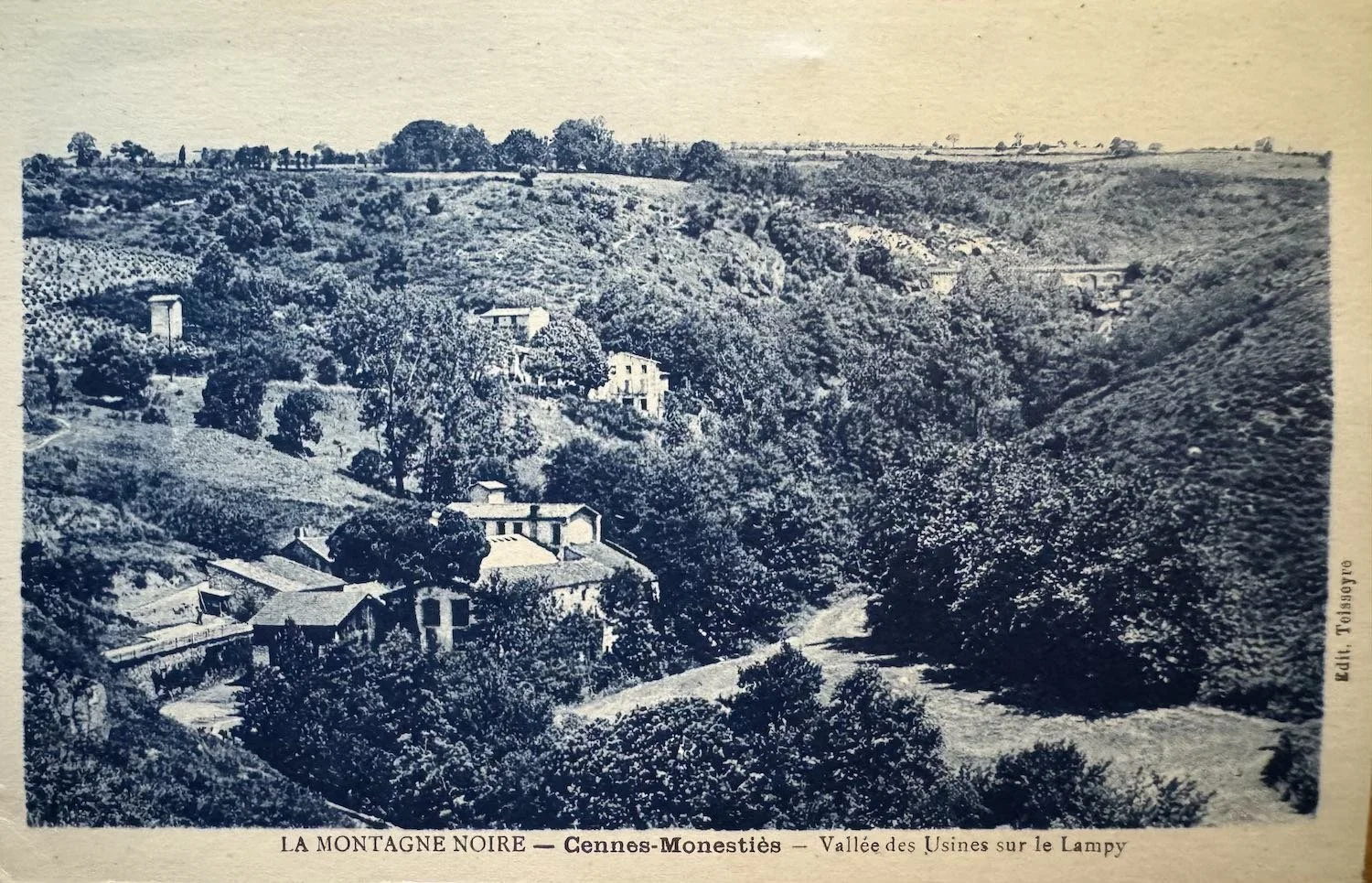

In the foreground of his viewfinder is a large granite boulder, partly submerged in the treeless, grassy slope. Beyond, as the valley curves away, stands an impressive collection of industrial buildings built beside a river in stone and lime. The nearest to the camera has timber cladding in the triangular apex of a tiled roof. It is overshadowed by the wide canopy of an umbrella pine. Behind it is the main building, entirely of stone, L-shaped and rising to four floors beneath a cascade of roofs. To their left is a cluster of small outbuildings. This is the Mécanique du Père, a cloth-making mill.

Across the river from the Mécanique is a pasture lined on the far side by a row of plane trees. Their shadows, laid across the grass by the mid-morning sun, are growing shorter. Further up the valley stands a fabric-dying factory called Badens. Beyond that, near the top of the frame, is a long wall built of stone joining the two sides of the valley together – le barrage. Behind it, unseen in the photograph, is a reservoir cradled in the top of the valley. There is a pair of arched openings in the wall through which in winter the water overflows before cascading down a fifty-metre cliff. This water joins the river that flows continually through two sluices at the base of the barrage and runs down the valley. It flows past the Mécanique du Père and then the photographer who waits a moment until a lone man in trousers and pale shirt, a labourer perhaps, steps out from the Mécanique. He walks between the outbuildings, stooped as if burdened by something. The photographer releases the shutter.

-

I am in the North of France where the land is flat but for the slagheaps or terrils that stand as monuments to a lost mining industry. Also called montagnes noires, they are now not so much noires or black as faintly green with grass and shrubs, and dashed with white lines – the bare trunks of silver birch trees. It is February 2024 and I am constructing the sets for a play, which takes place over temporal ellipses during a year in an imagined future. The story is set entirely in a tower block, where “civilisation” is sustained amid a barren, post-apocalyptic landscape. High in the tower is a “suspended forest.” On some of the trees grow hallucinogenic blue leaves used by the teenagers of the community to get high.

So, here I am with scissors cutting leaves out of blue, silk ribbon which I will then sew, one by one, onto the felled branch of a plane tree. But a part of me is in the Montagne Noire, where the photographer packed up his camera, descended that treeless, grassy slope, stepped onto the dusty lane and walked back to the village, the boulder and the Mécanique behind him.

Over ensuing decades, the Mécanique all but disappeared, leaving just the hollow remains of the mill's ground floor and, intact but fragile, the building of stone with timber cladding that stands beneath the umbrella pine. Five years ago, in February 2019, my husband and I bought that fragile stone building along with a slice of the surrounding land, including those hollow remains of the main mill. We called it “the ruin”. Then, a month ago, we expanded our plot by purchasing the slope with its submerged boulder.

I ought to go and discuss the system of pulleys that will fly the blue-leafed branch on and off the stage, but then I would have to stop sewing the leaves and daydreaming about our little slice of the Montagne Noire. If I was standing now by the boulder on the slope, I would not be able to see “the ruin”. Instead, I would be surrounded by oak and ash, and by chestnut and arbutus.

I want to get to know this valley. Why were there were no trees when the photographer took his photo? Why did it the become thickly forested and with these trees in particular? What was it like to work in those buildings of the Mécanique and why did that work stop? I am not sure where to start. So, I am starting here...