FEBRUARY-MARCH 2024 - Part 3 - Marks

Around 20,000 to 26,000 years ago during what is called the Late Glacial Maximum, ice sheets covered northern Europe and ice caps permanently covered the Alps and Pyrenees. The wide plain between the Pyrenees and the Montagne Noire was a steppe tundra, alternating between sparse grassland and semi-desert.

As the world warmed, the icesheets retreated and the icecaps on the Pyrenees began to melt. Precipitation increased. Water flowed into the plain giving vigour to once intermittent rivers, including one which the Romans named Atax, from the gallic Atacos, meaning spirited or very fast. Having headed west towards the Atlantic for some millennia, this river was captured and bent eastwards towards the Mediterranean.

-

There are conflicting reasons why our hills, our “highland” or massif, is called La Montagne Noire. I thought it was for the dark canopies of holm oak, but I read that perhaps it is because of the coal that was once mined here or for the often cloud-covered forests of pine on its cool, northern slope.

Of the rain that falls from those clouds, a proportion runs steeply north, down to the Mazamet fault, before being carried west to the Atlantic in the embrace of the River Thoré.

That which falls on the gentler, southern slopes flows south by way of many small rivers, each within its own small valley or vallon. One such river is the Lampy. Rising at about 800m in the forest of Ramondens, it descends first west, cresting over the village of Saissac before bending south to flow past the Mécanique du Père where once, many millennia ago, it stroked to roundedness the once hard edges of a granite boulder and then left it behind. Beyond the Mécanique it passes a village called Cenne-Monestiés.

On its journey onward it is joined by the Riplou, Fiou, Cantegril and L’Hort, tilting increasingly to the west as it levels into the plain and through the villages of Saint-Martin-Le-Veili, Raissac-sur-Lampy and Alzonne. Between Alzonne and the next village, Saint Eulalie, the Lampy gives itself up to the River Fresquel, itself flowing from further west in a region called the Lauragais.

Gathering force from the streams and rivers east of Montolieu, the Fresquel curves its way through Pennautier and then arcs north of Carcassonne before surrendering to the larger Atax, now called the River Aude. Continuing east, not so much spirited now as leisurely, it is joined by the Orbiel and Double Argent, denoting their past as sources of gold and silver respectively. Here, below the Minervois, the Aude flows north of Narbonne and then south of Beziers. And there it enters the Mediterranean – more particularly into that part of the Mediterranean called the Gulf of Lion, which stretches from Catalonia in the north of Spain to Toulon on the southeast coast of France.

-

These names, Riplou, Lampy, Atax and then Aude, are centuries old and known to me as long as I have been coming here. But they are just pencil marks, dust on the surface of time. We name things that are indifferent to us.

But without names, what can I say? That the forest is full of oaks both evergreen and deciduous? Would it not be more accurate to say that the forest consists mostly of downy, sessile and holm oak? Or perhaps, pubescent, English and holly oak? Or more properly, Quercus pubescens, Quercus petraea and Quercus ilex. I am a novice clutching at straws…and the internet. What is more, I am six or so hundred miles away in the North of France, realising an imagined forest for a piece of theatre. So, to keep myself sane while the tensions mount during the staging of an under-funded and over-ambitious production, I imagine myself in our real forest. Early in the morning on smoothed granite cobbles, I sit at a table and tap at a plant identification app and leaf through a book about the trees of Europe.

In my notebook I have drawn a rough plan of the terrain of the Mécanigue and have divided the parts of the forest into a grid as a way of positioning and locating each tree. Fixing them in space so that when I have learned how to identify them, name them with the names we have given them, I can also say that there they are. That the north-west part of the northern section is dominated by the downy oak and arbutus tree and the south-west section of the southern part by sessile and holm oak.

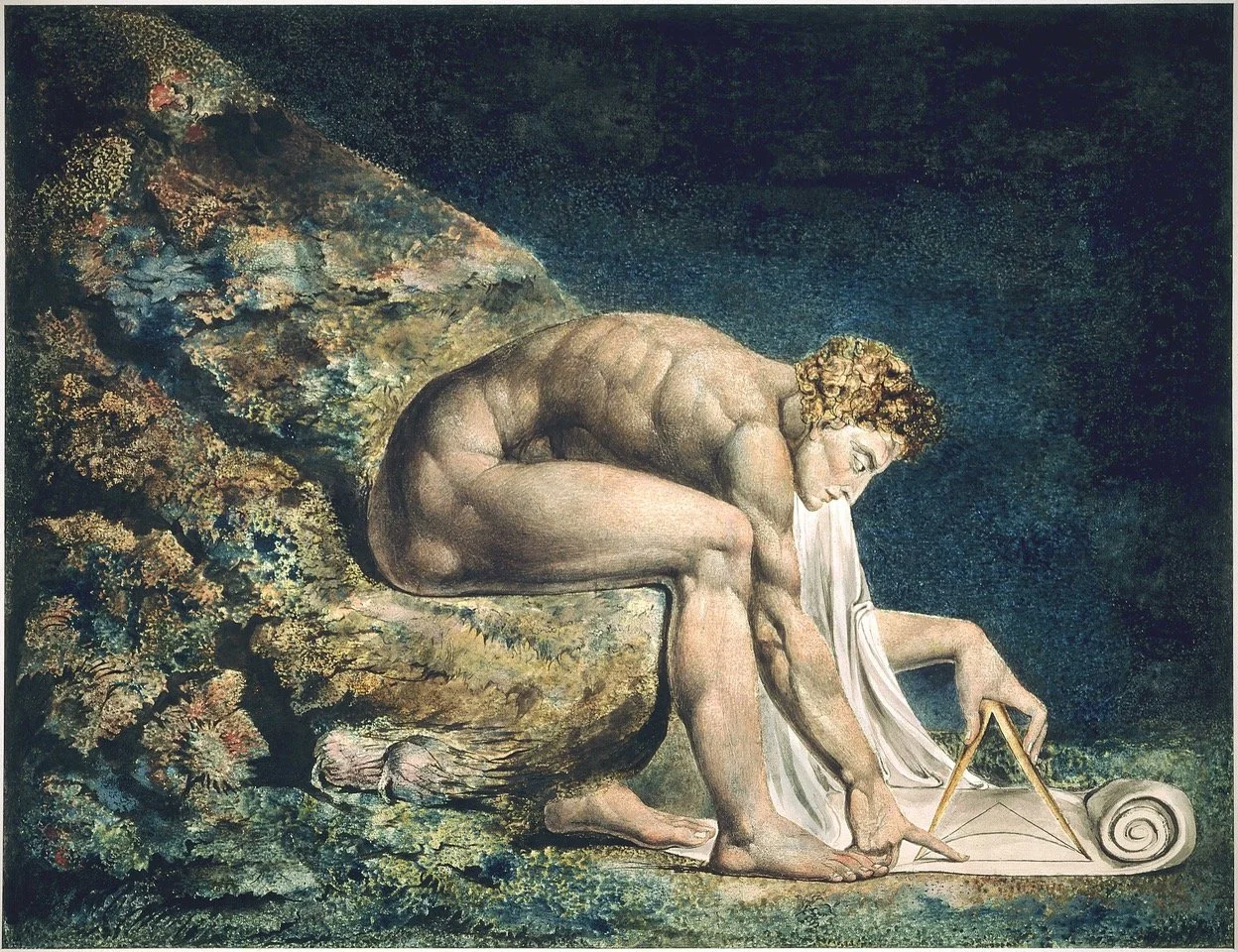

Willian Blake’s poem, The Book of Urizen, comes to mind…

“Times on times he divided, and measur’d

Space by space in his ninefold darkness,

Unseen, unknown; changes appear’d

Like desolate mountains, rifted furious

By the black winds of perturbation.”

Blake summoned Urizen as a totem of man’s Newtonian desire to measure and know, to control through knowing. Desire and magic bound by both scientist and priest. And yet…to name is to know. And to know is to really see.

It is eighteen years since I directed a performance of Urizen with music composed by the Italian composer, Carlo Crivelli, in a chapel in the hills outside L’Aquila in Italy. Soon after, the sleeping giant shifted. She shook to ruins the houses and roads that lay along the Paganica fault. What of such names then?

-

The trees that grew on the slopes of the Montagne Noire after the Last Glacial Maximum were pioneers. They and their off-spring, generation after generation, moved north, diversified and brought rain inland. This rain nourished the forests which, once surfeited, gave up the remainder as springs and streams giving urgency to swollen winter rivers that flowed down into the plain. Those rivers bent east and west depending on the density of stone and in so doing shaped the landscape.

Thanks to tree pollen carried by these streams, passed on to the Fresquel and then the Aude before being deposited in a sedimentary shelf in the Gulf of Lion, we know of the temporary disappearance of those pioneer forests during a cold interval from 10,000 to 10,800 years ago. This arboreal trajectory, led by epochal fluctuations of temperature and rainfall, is etched in the sedimentary shelf. It tells the story of climate. It narrates in turn the development of life and of its sustainability. It hints at the story of humans or rather, what was possible for humans.

First of hunter-gatherers, witnesses to the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic Periods, who inhabited the emergent arboreal cover of oak, birch and pine as these pioneer species crept gradually north. They also inhabited caves in the foothills of the mountains.

In the foothills of the Pyrenees, deep in the caves of Niaux that face north towards the Montagne Noire, they carved in the rock’s surface or drew with haematite for red pigment and manganese dioxide for black. They recorded that which was perhaps most comprehensibly vital to them, that which they hunted: bison, ilex, deer and horse. Nearer to the entrance, but equally hidden, they also made red and black schematic marks - dots and vertical lines. The vertical lines have been variously interpreted as clubs or the female form or as markers of the division of time.

-

Over the Bronze and Iron ages, forests began to be cleared for grazing of livestock and the growing of crops. Lines were drawn and the land was divided into squares and parcels. This process accelerated during Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages. So, it came to be humans who defined what was possible for the forest. Agricultural practices along with the increasing amount of timber needed to build houses and then heat them, transformed the landscape again.

In later centuries, the movement of people to coastal regions for trading led to the re-wilding of inland areas. As populations and thus the demand for food grew, so forests were cleared again.

Then we come to the time of the oldest, still living trees in which we can read the yearly story of weather and stress laid down in their growth rings.

I am making my dots and lines here, seeking with words to tell a story, to identify and divide, to recognise and know. As I try to carry myself forward to now, I find I am beckoned by words and facts to gather up and investigate. Dates and names. Explanations of how and why.

Memories too. Of a childhood spent in the canopies of trees in the Southwest of England. Trees I didn’t think to know the names of but who taught me that high above the ground at the most perilous extremes of a slender branch, two fingers delicately pinching a leaf will quell the vertigo that comes with climbing so high. And of a nascent adolescence, my own downy phase. In a den we had made of dead branches and frayed tarpaulin, a school friend called Simon and I explored each other on a bed of leaf and loam amongst scattered ring-pulls and distended beer-can yolks. There, below the protective skirts of a holly tree, another sleeping giant shifted to wakefulness.

Perhaps, as I step into our forest and seek to understand the trees within it, I am also stepping into my past and seeking to understand the memoires there. Time thickens like the trunk of a tree and deepens like the sedimentary shelf in the Gulf of Lion.